As the International Seabed Authority (ISA) convened last month to continue work on regulations to allow the industrial mining of the ocean floor, China extended its domain over the deep sea.

The United Nations organisation headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica, approved the country’s fifth mining contract, meaning China holds more mining claims than any other nation. China now has the right to explore and potentially exploit 238,000 square kilometres (almost the size of New Zealand) of the deep sea in areas outside national jurisdiction for cobalt, nickel, copper and other valuable minerals.

To date, the ISA has issued 30 exploration licences to multinational corporations, start-ups and state-backed companies that cover more than 1.3 million square kilometres of the seabed.

China, which has been one of the ISA’s biggest financial benefactors, also signed a memorandum of understanding with the organisation to establish a joint deep sea training and research centre in Qingdao, to be operated by the State Oceanic Administration.

China’s growing influence comes at a pivotal time for the ISA. The secretary-general, Michael Lodge, private mining contractors and pro-mining states are pushing to complete a “mining code” by the end of 2020 so exploitation of the seabed can commence.

The stakes are existentially high.

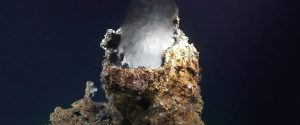

The deep ocean holds what is believed to be the world’s largest reserves of the metals needed to make electric car batteries, wind turbines and other technologies essential to weaning the world from fossil fuels and combating climate change. But the little-explored seabed also harbours unique ecosystems and an untold number of rare and undiscovered species whose genetic code could be the source of new medicines and other biotechnologies. Mining would directly destroy those habitats with an unknown impact on the surrounding ocean and the global climate system.

The ISA’s 168 member states are charged by the UN’s Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) with promoting the mining of the seabed while, contradictorily, protecting the deep ocean’s fragile ecosystems as the “common heritage of mankind”. Under that doctrine, the financial spoils of seabed mining must be shared among nations.

That tension between exploitation and preservation of the deep sea has been percolating for years, but it intensified at the July meeting of the ISA Council, the organisation’s policymaking body. One after another, national delegations took the microphone to call for strong environmental regulations and pushed back against the 2020 deadline.

“The quality of the mining code is more important than any superficial deadline,” Germany’s delegate told the Council, echoing a diverse group of nations with competing interests, from South Pacific island states and European countries to even pro-mining nations like Japan.

Or as Jamaica’s representative, Kathy-Ann Brown, tartly put it: “The idea that we can get this done in a year and a half is fiction. It’s not real.”

China, uncharacteristically, did not weigh in on the debate.

“They weren’t as forceful as they have been at previous sessions,” says one longtime observer of the ISA. “I don’t think anything will happen if the Chinese are against it, but they were more in a ‘let’s listen mode.’”

Kristina Gjerde, a senior high seas adviser at the International Union for Conservation of Nature, notes that China may not be in a hurry to mine the seabed given its access to significant sources of terrestrial minerals. Chinese companies own eight of the 14 largest cobalt producers in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is the source of 68% of the world’s supply of the mineral. China also produces 80% of the global supply of cobalt chemicals.

“They may want to wait until they have access to technology in compliance with the best environmental standards,” says Gjerde, who has attended ISA meetings for the past five years. “The pace that’s been kept up for the 2020 deadline seems to be purely for the convenience of a couple of companies most advanced in their technology.”

At the past four ISA meetings, China has tilted toward the pro-mining faction of nations that includes Japan, South Korea and Russia.

At the August 2017 Council meeting, for instance, China’s delegate cautioned against adopting overly stringent environmental rules that would hamper mining contactors. “We believe that environmental rules in terms of environmental management measures should have substantial proof that there is a risk of environmental harm,” the delegate said.

Then at the July 2018 Council meeting, China’s delegation noted that “there should be a reasonable interest struck between exploitation and protection of the environment”.

At last month’s Council meeting, the country’s permanent representative at the ISA, Tian Qi, led a 15-member delegation, one of the largest in attendance. “We should aim at practicality,” Tian told the Council as delegates discussed environmental regulations for deep sea mining.

But China faces challenges straddling the line between exploitation and environmental protection as the complex geopolitics of the ISA grow ever more complicated. With the 2020 deadline approaching, nations that have rarely attended ISA meetings or participated in Council deliberations have jumped into the fray.

Developing nations that believe they stand to benefit financially from seabed mining – including those that are sponsoring states for mining companies and would reap taxes and fees from exploitation – are pressing for the regulations to be completed by the deadline.

On the other hand, some small South Pacific island nations whose waters are closest to areas to be mined are advocating for strong environmental protections. Countries whose economies rely on terrestrial mining – Chile, Australia, some African nations – are urging caution in proceeding with seabed mining. (The United States is not a signatory to the Law of the Sea treaty and thus is not a member of the ISA though it maintains observer status at the organisation.)

The ISA makes decisions consensually, so theoretically a tiny nation like Nauru, with a population of 13,000, has the same power to determine the fate of the deep ocean as China. But there is yet little agreement on a host of issues that makes meeting the 2020 deadline problematic.

The economic model for collecting and sharing the financial bounty of deep sea mining with member states remains unresolved. Nations with onshore mining industries, meanwhile, have requested that a study be conducted on the potential impact of seabed mining on terrestrial mineral production.

There does appear to be widespread agreement that before mining can start, regional environmental management plans (REMPs) should be put in place for each of the three types of deep sea ecosystems to be exploited.

However, only one has been completed – and is it due to be revised. REMPs will rely on years of environmental baseline data on the biology of the claim areas that mining contractors have been required to obtain since 2001. Furthermore, National Geographic revealed last month that the data, which has been kept secret by the ISA, has only been sporadically collected and much of it is not of the quality needed for valid environmental baseline studies. The ISA body that reviews mining contractors’ compliance with exploration regulations told the Council in July that some contractors continue to violate environmental data collection requirements, though it declines to identify them.

There also seems to be consensus that the environmental standards and guidelines that will govern the implementation of the mining code should also be completed before those regulations are adopted. But those standards and guidelines have yet to be written.

“I think the Chinese assumed correctly there’s no way ISA is going to keep to that deadline and there was no use for them to be seen as someone trying to whip the horse to meet the deadline,” concluded one observer.